Tcl is the programming language that goes hand in hand with VHDL. You may choose to learn Verilog instead of VHDL, but you will be exposed to Tcl no matter which HDL you decide to use. That is because most FPGA-related programs, such as simulators and synthesis tools, use Tcl in their command shells.

Having a standardized scripting language for software tools is actually very clever. It enables you to transfer your scripting skills from one tool to the next. That would have been impossible if every vendor had invented their own command language. Anybody here old enough to remember mIRC scripts? Well, I was an expert.

Another advantage is that you can reuse code in several tools and platforms. You can transfer them from one vendor to another and use them in different stages in your verification process, for example, generating input to the DUT both in simulation and in the lab.

Tcl, Tickle, and Tcl/tk

Tcl is an acronym for “Tool Command Language”. It’s spelled with lowercase ‘c’ and ‘l’ because it’s normally pronounced “tickle”, not tee-cee-ell.

The success of Tcl as a tool command language probably comes down to the simplicity and power of the language. Tcl’s core functionality is very basic, and it would be relatively easy to incorporate custom commands into the Tcl shell. But still, you can write complex programs with it.

Furthermore, many existing extension packages add functionality to Tcl. There is even a quite well-known GUI toolkit for it; Tk. Sometimes Tcl and Tk are mentioned together as Tcl/Tk, but the latter is really an extension of the former.

Tickle is both ingenious and frustrating

Tcl interpreters follow a basic set of rules, and that’s what makes it a good tool command language in the first place. But this can also be a source of frustration when you try to accomplish complex tasks by utilizing the freedom that Tcl offers.

Everything is a string

A core concept in Tcl is that every object is a string. Strings, integers, lists, and arrays appear as strings to the programmer. And they can be manipulated and treated as strings as well.

% set listA [list 1 2 3]

1 2 3

% set listB "1 2 3"

1 2 3

% string match $listA $listB

1

%

In the code above, we first declare “listA” containing the numbers 1, 2, and 3. It is declared by using the special “list” command. Then we declare “listB” as a regular string containing the text “1 2 3”.

As we can see from the last line, the two variables now contain the same string: “1 2 3”. They are equal, as indicated by the return value “1” (also a string) from “string match”.

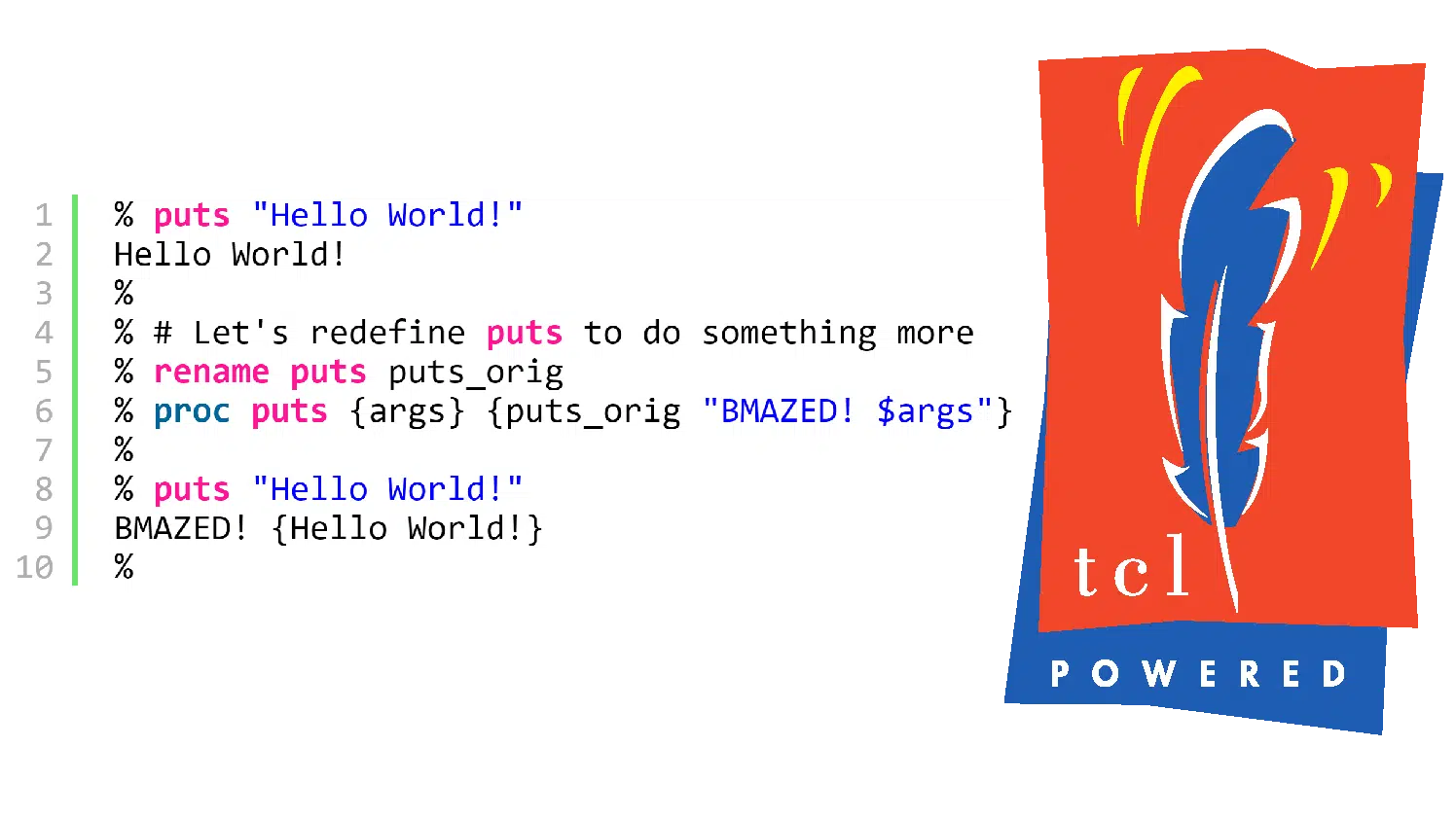

Everything can be redefined

As already mentioned, everything is a string in Tcl. That includes source code as well as most commands and keywords. Therefore, they can also be redefined, like any string variable can. While this is arguably a cool feature, it can easily mess with your mind if you start changing standard keywords.

% puts "Hello World!"

Hello World!

%

% # Let's redefine puts to do something more

% rename puts puts_orig

% proc puts {args} {puts_orig "BMAZED! $args"}

%

% puts "Hello World!"

BMAZED! {Hello World!}

%

Consider the code above. I have simply opened a Tcl shell (“tclsh”) on Linux and typed in some commands. In Tcl, “puts” is the standard command for printing text to the console.

On the first line, we use it for printing “Hello World!”. Then, “puts” is renamed to “puts_orig”, and we declare another function in place of “puts”. Finally, when we call “puts” for the last time, it is our redefinition of the command that gets called.

Substitution and evaluation

Tcl relies heavily on variable substitution. Much like in bash scripts, words that are prefixed with a dollar sign (‘$’) are treated as variables.

% set myVar "Hello World!"

Hello World!

% puts "myVar: $myVar"

myVar: Hello World!

%

In the code above, we first declare a variable by using the “set” keyword. Then, we print it to the console by substituting its value by prefixing it with ‘$’ when calling “puts”. As we can see, the value of “myVar” is printed where we prefixed it with the dollar sign.

But things can quickly become unmanageable if you go nuts with substitutions. Consider the horrific code example below.

% set myVar {$myOtherVar}

$myOtherVar

% set myOtherVar "puts HAXOR"

puts HAXOR

% eval [expr $myVar]

HAXOR

%

We first declare a variable that contains a reference to a dollar substituted value that doesn’t exist yet. Then, we declare the referenced variable “myOtherVar”, and set its value to be the command (string) “puts HAXOR”. In the end, we evaluate the expression. The innermost command gets run, and “HAXOR” gets printed to the console.

Unusual variable scopes

Another thing that Tcl newbies often struggle with is how variables are scoped in Tcl. If you don’t understand this correctly, you may modify objects that don’t belong to your program or widget.

Tcl’s subprograms are procedures, and these may have local variables. But there are also global variables and variables belonging to namespaces or classes.

Further complicating the matter, there are many commands to declare and access variables in or outside the scope of the code you are writing. It’s well worth the time and money to invest in a proper Tcl course that explains these things for you.

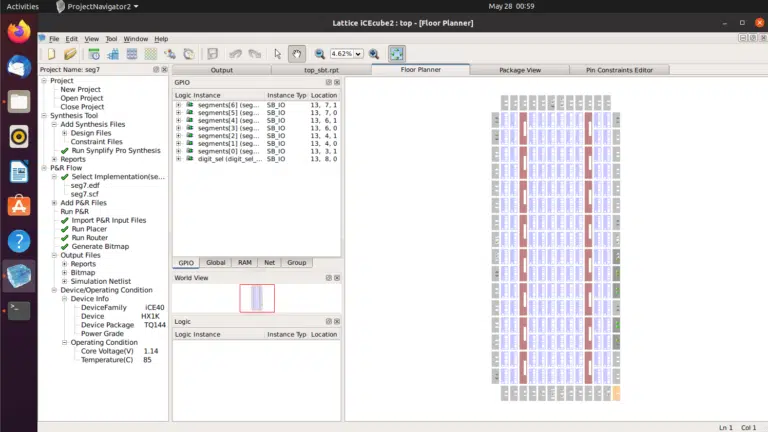

Tools supporting Tcl

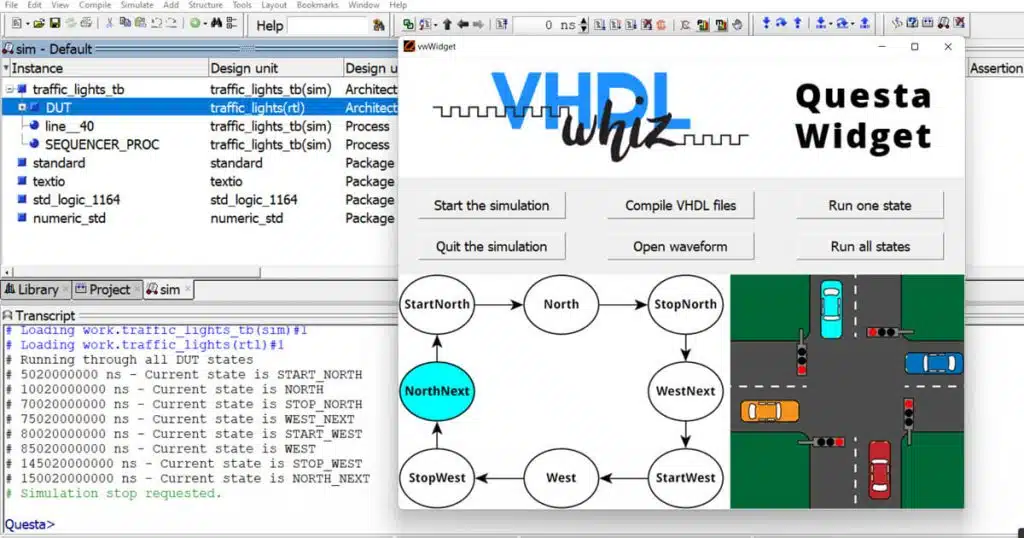

Questa/ModelSim is where I use Tcl the most. Take a look at the command reference, which has extensive descriptions of all the commands that you can use in the built-in Tcl shell. Do-files are ModelSim scripts. But they are really just Tcl files, and you can program Tcl in them as well.

Tools that support Tcl include:

- Questa/ModelSim

- Riviera-PRO

- Synplify Pro

- Altera / Intel Quartus Prime

- Vivado Design Suite

- Xilinx ISim

Get started with Tcl today

Tcl has been around for over 30 years, and it isn’t going away any time soon. The good news is that when you learn Tcl, you automatically have the skills to do advanced scripting in many different software tools.

A good resource for learning Tcl is the official Tcl Developer Xchange.

If you have a Debian flavor of Linux available, you can easily install a Tcl interpreter by issuing the command “sudo apt install tcl”. The shell can then be started with the ‘tclsh’ command. On Windows, you can follow this guide. You can also program Tcl directly in the ModelSim console.

The beauty of Tcl in Questa/ModelSim is how well it integrates with VHDL. From its Tcl console, you have full access to all VHDL objects for reading and writing. That’s why I focus on using Tcl for creating the testbench infrastructure in my new course. 👇

New Tcl course

* Update 2022

Check out VHDLwhiz's new Tcl course with 18 video lessons!

Course: Tcl scripting for FPGA engineers

Sir, can you please let me know, is it worth learning perl for chip designers, if not, we must go for which language after VHDL…?

I would say that Bash scripts in combination with Makefiles are most commonly used in the VHDL and FPGA design process. Don’t think I ever saw a serious FPGA project on Linux that didn’t use that combination. It might be a good idea to read up on those.

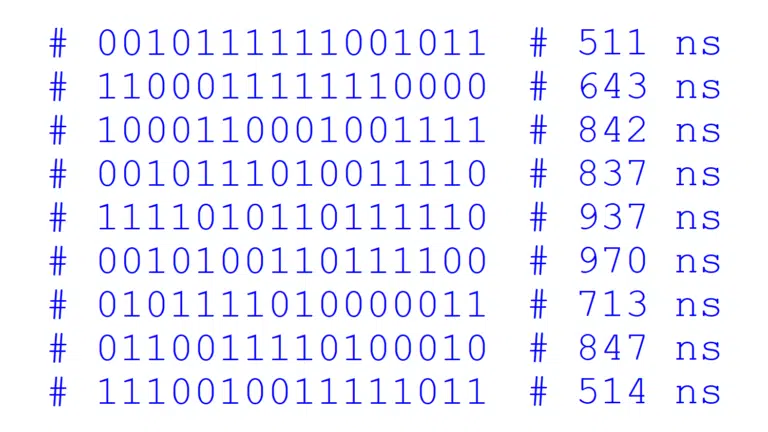

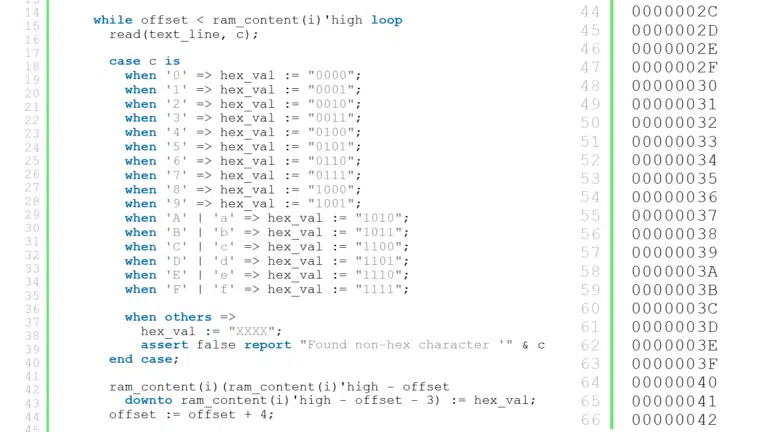

As for Perl, I’ve seen that used a lot too, but mostly for legacy projects. I think Perl has been mostly replaced by Python as the go-to scripting language. I’ve often used Python for things like generating RAM content or testbench patterns in VHDL, things that VHDL isn’t any good for. Typically, I would use a Makefile to tie everything together by calling the Python script and then the VHDL simulation or synthesis.

I should add a disclaimer that I may be biased. I’m an expert in Python, but I barely know Perl.

Thanks for a wonderful reply……And just wanna tell you that you website has one of best learning sources for VHDL with simplified content.

Thanks again …….?